Ennio Morricone & John Williams – Princess of Asturias Award 2020 – Special Article

The recent announcement of the 2020 Princess of Asturias Award for the Arts to the legendary composers Ennio Morricone and John Williams (read news), has unleashed a multitude of articles, news, and debates, in all the physical and digital media in the country.

Today we bring you a special article written by the pianist and composer Pablo Laspra, Director of the “Oviedo FilmMusic Live!” festival, for the Asturian newspaper La Nueva España. This article has been published in today’s supplement, Sunday June 14 (read more), and Pablo Laspra has shared this special article in a collaboration with SoundTrackFest.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE MUSICAL SCRIPT IN THE CINEMA

Last week, all film music lovers received wonderful and long-awaited news that, although they came at a bad time for culture in general, due to all the limitations that artistic and cultural events must follow by COVID-19, it highlighted at last the universal importance of storytelling through music. And we must not forget that the cinematographic musical narrative is not just “wallpapering” a film with music, nor it is just underlining and highlighting what is already obvious in the film. Film music has independence, a life of its own, and sometimes is sibylline in its intentions: it has enormous importance and power, but is generally underestimated.

The new symphonic poems, the new musical narratives, have their obvious evolutionary development in the soundtracks, although it is true that it is difficult to group all film music in the same genre (in terms of quality). Currently this is one of the most prolific artistic genres and with the most followers. These popular musics have also evolved off-screen in concert mode, or through live-to-picture events, or even in compilations to improve the ability to concentrate while studying (replacing the usual compilations by Mozart and Bach). But our protagonists have not stood out above all the others just for this, although they have partially surrendered to this type of business.

The figure of Williams was a point of inflexion in the orchestral and melodic treatment in film music. While other contemporary composers tried to introduce synthesizers into film music (where Williams also did some experiments), the sound of Williams was based on a new symphonic style that some call plagiarism or say it just exposes what was already invented. But only he made it shine above all others, making it evolve and stand out to become a reference. A reference that has managed to win over the public, because it is not only about telling musical stories, and driving the film towards a specific plot point. The music that has no apparent function in the film or that does not meet its needs, is not only bad music, but in addition, if it is not remembered, either because of its difficulty of remaining in the minds of the viewers or because of its monotonous aesthetics, then it couldn’t get any worse. And none of that has been a characteristic of Williams’ music.

Great are his epic moments in “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial”, full of brilliant scherzos and quasi-fantasies, that fill the film with both speed and an endearing attitude towards an alien that is not visually pleasing. Or the wonderful fanfares composed for the saga “Star Wars”, “Indiana Jones”, or even “Superman”, although many people consider that they are the same theme and fail to differentiate between each one (something perhaps logical to all those not used to his fanfares as they have relatively similar orchestration and motivic developments). Or how he has managed to create great film classics such as “Schindler’s List”, “Jurassic Park”, “Harry Potter” or its predecessor the funny “Home Alone”.

Years ago, in one of the conversations I had with Kevin Kaska -one of his main orchestrators at the time- I was struck by the special heart and soul that maestro Williams instilled in the melodic development of the themes of his films: he always tried to make them “hummable”, relatively memorable, and he subtly hid the titles of the films (in English of course) in the main theme of many of his pieces. Perhaps it was a fabulation of the moment, or perhaps it was another indication that the maestro knew the formula for success in orchestral film music, and although many others have worked the symphonic sound within the cinema, they have ended up with different luck. What else could define the success of a soundtrack in an era without social networks, without the Internet, without viralization other than magazines and supplements that analyzed this art briefly? Perhaps in Williams’ case, the secret was in his way of working with what we could call today a new American musical nationalism: taking the best of his maestro Korngold and some predecessors like Elmer Bernstein or Miklós Rózsa, mixing it with the beautiful and descriptive melodies of Copland or Grofé, going through the orchestral treatment of great composers like Mahler or Holst, and reusing previous musical structures that worked well on the image. He knew how to create a simple but effective sound, existing but new, and effective but discreet in its aims.

Many will say that plagiarism and copying existed, but even though there were great similarities between many of his pieces (cinematographic and concert) with pre-existing works and styles, he made them his own, he made them everyone’s, and made them universal.

In Morricone’s case, perhaps from the beginning he was a little more direct in his intentions: he never cared about criticism, he never let himself be manipulated by directors and producers, and did what he did best: tell stories through music. Both were filmmakers, with capital letters, and they didn’t subordinate their music to the film, but made films with their music. Although for more than a decade he dedicated himself almost exclusively to the western style, from the 70s and on, his links and political intentions within Italian cinematography had a peak.

Morricone started from scratch, living badly and making arrangements of songs, and he has known how to reach the top, sowing in his vast way a great quantity of musical and cinematographic masterpieces. He’s much more varied in terms of genres and styles than Williams – not that this makes him better, or worse – and although the western is the type of film for which he’s best known, he’s been capital with directors as emblematic as Gillo Pontecorvo, Bernardo Bertolucci, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Elio Petri. Morricone is part of European cinema, and European cinema has also known how to embrace his art; and not only Italian cinema (he has worked a lot in France and sometimes in Spain) but also in English-speaking cinema: his scores for the film “The Mission” (which received the greatest injustice of the Oscars, not winning it that year), or in Brian De Palma’s films such as “The Untouchables”, are clearly memorable.

Morricone is epic, he is intimate, he is extravagant, he is delicate, he is romantic and also wild. There are many Morricones in Ennio Morricone. And despite his appearance (not a true one) of “distant maestro with a haughty gesture”, he is an endearing person, with great sensitivity and extreme skills, neat in his melodies -even in the simplest ones-, and delicate in the treatment of the narrative story.

Hopefully, and although the time is not the most propitious for these two beloved winners to physically come to collect their award, the miracle will take place, and as it happens in many of their good films, we will have a happy ending and we will be able to enjoy their presence in our region. The step is taken, and the recognition is more than fair. Now we just have to let fate leave us with a new hope.

¡Bravo, maestros!

Article by Pablo Laspra Ferrero

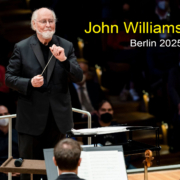

Pictures by Gorka Oteiza